Yesterday

Frank Sinclair gave me a copy of the revised (and second) edition of

his book, "Without Benefit of Clergy." It contains some new material, so

even for those of you who have already read it, it's well worth a

second look. The preface alone--delivered succinctly, and with

characteristically dry wit-- makes for a delightful read.

Now on to the meat.

I've

touched on the issue of polarity a few times in the recent past, but I

thought it might be worthwhile to explore the idea in more depth; this

time, in the context of my wife's question of a few weeks ago, to wit,

"what do we need negativity for?"

The subject

of negativity is a "hot" one--both in the Gurdjieff work, and in other

spiritual disciplines in general. For one thing, there's this

presumption that we can rid ourselves of it... that saintly halos and

angelic beatitudes await those who conquer these lower impulses we all

have. For another, that our negativity is "bad," that we shouldn't be

negative, that we should not express it (Gurdjieff's classic premise),

etc.

So why, indeed, does negativity exist?

As I said to Neal during our morning walk a few weeks ago, negativity must exist. It is essential. Both we--and the cosmos-- need it simply because currents cannot flow without two poles to move between.

The whole universe is built this way. There's no exchange of energy without polarity: nothing happens.

Material reality arises from the flow of energy and the tension between

poles. If we propose a cosmos without polarity, there is no movement.

It is a static entity.

So we tiptoe to what is

for me perhaps the most interesting part of this question: negativity

and its relationship to materiality.

We are told, in Beelzebub's Tales to His Grandson,

that God created the universe because the Merciless Heropass (time) was

destroying the place of his existence. That is to say, God created materiality to counteract

the effects of time. Space and time are not, in other words, a

"space-time continuum." They are fundamentally different

entities--wedded to one another, if you will, but with very different

genetic backgrounds.

This critical distinction between time and space is more interesting than ever in light of the theories of

Petr Horava, as reported in the latest issue of

Scientific American.

Mr. Horava's theories--which, by separating space and time at high

energies, offer resolutions to some of the more perplexing

contradictions between quantum mechanics and classical reality-- support

Gurdjieff's vision.

We might suggest that

materiality--space, the universe, all the arisings of materiality--in

and of itself creates the negative "pole" which creates and supports the

flow of energy emanating from God. In this model, we can envision a

vast and cyclical engine created by the flow of energy from the divine,

into material reality, and then back into the divine... in short, the

ray of creation, more or less as Gurdjieff described it to Ouspensky.

This

offers us a new point of view about materiality and its relationship to

negativity--one I paint with broad brushstrokes, which will require

some intuitive leaps to grasp.

So put your jumping shoes on.

In this expansive point of view, the universe of materiality itself, in its totality,

is the functional "holy denying" force of the cosmos. It is roughly

equivalent to "sin" in the Christian religion, or "suffering" in

Buddhism. By analogy, the very expression of materiality itself becomes

an anguished separation from Godhood, a "fallen" condition which must be

overcome so that the higher forces which it attracts--which, indeed, it

actually creates the conditions to attract--can gather and return from whence they came.

Hence, we equate materiality itself

to negativity--one of the most vital forces in existence, which in and

of itself creates all the possibilities for evolution. No matter what we

do, the fact and consequences of materiality are inescapable. This is

one of the points of Dogen's sophisticated arguments about cause and

effect (per the Zen parable of the red fox, as recounted in his Shobogenzo.) It is furthermore the central axis around which St. Augustine's premise of original sin turns: we are inherently "sinful," that is, wedded to the materiality from which we spring, and fundamentally separated from God by our very physical existence, which (equally) stands as the root of our suffering, as the Buddha would have it.

In

a universe that supposedly offers us the option of free will and

choice, the idea of inherent sin doesn't make much sense. After all, if

we can choose not to be sinful, then we are not inherently sinful. If we

understand "sin", however, as being as fundamental and as simple as

material existence itself-- that is, as being the negative pole that

"stands against" the existence of God -- then it is indeed inherent.

St. Augustine's arguments make more sense from this point of view than

from any moralistic sensibility.

...Readers

should take note that while I am, it is true, examining the word "sin"

here in a much larger context than the narrow traditional parameters

defined by "good" and "bad," the effort to reinterpret the idea of

exactly what sin "is" has an equally longstanding tradition--Gurdjieff

himself did it, and the question of exactly what sin consists of is

still a very active one which ever lies at the root of all Christian

practice.

In this regard, we discover that while we may not be what makes it possible for God to exist, our materiality itself might certainly be what makes God meaningful.

This, in turn, goes a few steps in the direction of explaining why Gurdjieff contended that God needs us as

much as we need God. If we were to put our tongues in our cheeks (or,

perhaps, our feet in our mouths) we might say that God needs sinners to

save.

It's what keeps him busy.

This

tension between materiality and Godhood serves as well as a central

premise in Paul's letters, where forces of spirit and flesh find

themselves in eternal opposition. Paul's continued emphasis throughout

his teaching is about resolving the dilemma of material existence when

measured against the Holy Spirit.

The Buddhist

invocation of Dharma--truth, totality, or reality, depending on just how

we choose to pitch our interpretation-- attempts to transcend the

entire question of materialism by radically folding polarity, and its

resolution through action, or the flow of energy, into a single whole:

enlightened consciousness (=Godhood), time, and the material world, a

tripartite cosmological relationship. I am not so sure there is any

significant difference between this and the Christian position on this

question.

Here's what I see as the

central dilemma of both Buddhist suffering, and Christian sin.While we

find ourselves irrevocably (until death) immersed in the flesh, a deep

and unexamined part of ourselves fundamentally rejects this

material condition. A tension arises because of our very refusal to

accept what we are, accept the flesh, accept our separation, accept the fact that we are going to die.

So

we live in a perpetual, deeply rooted, unseen, and unquestioned state

of disbelief and refusal. Disobedience, in the Christian world view;

suffering, from a Buddhist's point of view.

This condition is organic, in the sense that the whole organism lives in a state of inner denial about the actual conditions we are in.

Gurdjieff's conclusive admonition at the end of Beelzebub

is that the greatest (and perhaps only) hope for man would be for him,

during the course of his lifetime, to irrevocably and constantly sense

the fact of his death.

This points us directly towards an ongoing practice which learns to accept the materiality.

Admittedly, this stands in opposition to the standard religious

practices of denial of the flesh... it actually, and perhaps

perversely, constitutes an acceptance of the flesh... but then, of

course, Gurdjieff's premise always was that the world's major organized

religions had this one all wrong from the get-go.

Why, one might ask, ought this "acceptance of our materiality" make a difference?

In order to understand that, one must first ask, why are we here at all?

We

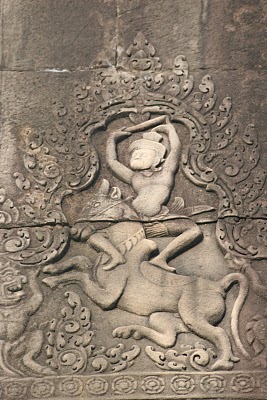

are assigned a cosmological role in playing one end of a stick. In the

Gurdjieffian cosmology, materiality is the negative pole which attracts

the energy needed to maintain the universe. Man is in a position to play that role consciously,

and it is only insofar as he does so that he attracts the "maximum"

amount of higher energy, or "help", that can be mediated through his

material existence. (This understanding also relates, of course, to the

taoist ideas of man as a "nail" between heaven and earth.) The

discerning reader may intuit other interesting parallels between various

esoteric philosophies and this question of polarity and the flow of

energy.

One ought, I think, to avoid

philosophical discourse of this kind--and at this length--without

getting back to some practical questions, that is, questions about our

individual inner practice.

In order to understand this more fully, then, a conscious investment in our materiality is necessary. We must engage in sensation--inhabit what we are--be what we are, in order to play our role.

And

being what we are is not trying to be angels. It is the inhabitation of

the flesh, the acceptance of our inherent nature, the seeing and

investment within the very fact of our material nature, our negativity,

in all of its manifestations. As Martin Luther said, "since we must sin,

let us sin boldly."

We have no real choice

but to inhabit this material existence. Rather than escape it--escape

the sensuality, the materiality, the struggle and the tension-- let us

embrace it. Only by living fully within the exact conditions we are in

can we fully understand that all the conditions are necessary.

Everything that is "wrong"--and right-- about material existence forms the ground floor of why we are here at all.

May the living light of Christ discover us.