We have visited the question of the difference between inner and outer impressions on a number of occasions recently.

Paul addresses what may be the same question in chapters 1 and 2 of his letter to the Romans.

It

is all too easy to interpret Romans 1: 24-32 as a condemnation of

homosexuality and other aberrant sexual practices. However, I believe

Paul takes considerable pains to explain that in these two chapters, he

is speaking about the difference between inner practice -- the receiving

of impressions through the six inner flowers, impressions "sent from

God" -- and outer practice -- that is, receipt of impressions through

the five ordinary senses.

He specifically cites the incorrectness of mixing an understanding gained through inner impressions with outer impressions:

"21.

Because of that, when they knew God, they glorified him not as God,

neither were thankful; but became vain in their imagination, and their

foolish heart was darkened.

22. Professing themselves to be wise, they became fools,

23.

And changed the glory of the uncorruptible God into an image made like

to corruptible man, and to birds, and four-footed beasts, and creeping

things." (King James version, Romans 1: 21-23)

On the surface,

this appears to be about the practice of idolatry, but given the

standard early Christian practice of depicting fish, birds, lions,

lambs, and so on as symbols of Christ--which was never condemned--, I

feel it is unlikely that Paul is referring to the using of such imagery

per se.

Instead, he appears to be discussing man's habit of turning inner

experience against itself, literalizing it, and making it an object of

the five outer senses. In this sense he is arguing against what the

Buddhists call attachments.

Paul was probably well aware of the

danger of misinterpretation of his allegory, because in the very next

chapter, the first verse warns people

not to use his words as an excuse for judging other people's habits.

"1.

Therefore thou art inexcusable, O man, whosoever thou art that judgest:

for wherein thou judgest another, thou condemnest thyself; for thou

that judgest doest the same things." (KJV, Romans 2:1)

Paul

finally wraps up the discussion about judgment, law, Jews, Gentiles, and

circumcision at the end of chapter 2 by making it quite clear that the

circumcision he speaks of has nothing to do with the standard outward

Jewish practice of

physical circumcision:

"28. For he is not a Jew, which is one outwardly; neither is that circumcision, which is outward in the flesh:

29.

But he is a Jew, which is one inwardly; and circumcision is that of the

heart, in the spirit, and not in the letter; whose praise is not of

men, but of God." (KJV, Romans 2: 28-29)

We are perhaps reminded

here of Solomon's wrap up at the end of Ecclesiastes--all of which is

critical analysis and condemnation of our intense attachment to

outwardness--in which he says:

"Let us hear the conclusion of the

whole matter: fear God, and keep his commandments: for this is the

whole duty of man." (KJV, Ecclesiastes, 12:13)

Reviewing all this left me with the question of exactly what circumcision "of the heart and in the spirit" means.

As

it happens, being engaged in the audio editing of Beelzebub, I am

working on the chapter "Beelzebub in America," and there is a passage

discussing the practice of circumcision in some detail. Since the

subject itself does not come up that much in esoteric literature, it

must have some specific significance we have not considered in enough

detail.

One of the most obvious possibilities here is that we are

looking at an analogy which teaches us that we must shed the outer in

order to stand naked before God in our most intimate parts. I think we

can all agree that makes a great deal of sense. If this is correct, the

choice of circumcision as a symbol contains some magnificent

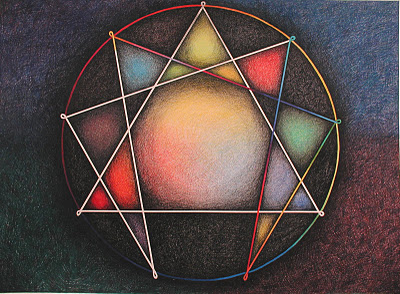

understandings that relate, surprisingly enough, to the enneagram, which

is not a place one would usually look when discussing circumcision.

The act of circumcision involves encirclement; in an act of

encircling,

moving in a circular motion, one cuts the foreskin, thereby separating

the outer from the inner. The outer is discarded, leaving only the

essential part: the reproductive organ. And it is this reproductive

organ itself that stands naked before God. We see therefore that the

idea of circumcision mirrors the idea of completing the enneagram,

sealing the inner vessel.

We may suppose that circumcision "of

the heart" may well have something to do with eliminating all that is

emotionally unnecessary except the worship of God itself--which is

precisely what Solomon advocates in the last lines of Ecclesiastes--,

and laying the heart bare to accept the "reproductive power of God,"

that is, the implicit power of Godhood made flesh through the Holy

Spirit, which is what Christ called everyone to. We see here an

inference that there must be an emotional cleansing within.

Circumcision

"in the spirit" refers to a location. I believe that taken in the

whole, the phrase "of the heart and in the spirit" comes very close to

referring to a specific kind of yoga work involving a specific location

and a specific part within the being. We need look no further than the

yogic symbol of the

linga, or

male phallus, to know that reproductive parts have been used as an

allegorical reference for spiritual work since ancient times. The fact

provides one more peculiar and provocative link between Paul's letters

and traditional yogic practice.

I know some will argue it isn't

possible that Paul could have been referring to anything like this. Of

course, it is quite possible. Jesus Christ clearly taught of an

esoteric set of principles; as an initiate, Paul had to be familiar with

them. The very fact that he refers to "inner circumcision" implies that

he was speaking in parables, the same way Christ did. And for my own

part I believe it is patently impossible that a man at Paul's- or

Christ's- level could possibly have remained ignorant of yoga, a

long-standing religious school whose practices had to have been known

all over the middle East by the time he was born.

We know that

the enneagram represents two specific sacred laws within the universe.

We also know that circumcision was a sacred law within the Jewish

community. So when Paul refers to "inner circumcision," he definitely

refers to following sacred law according to inner principles. For

myself, the

inner study of the enneagram exemplifies exactly this kind of activity.

When

we take these two chapters together, we also see that any

interpretation of Christianity that insists on literalism in biblical

text can only sustain itself through a willful invocation of ignorance.

When

we consider Gurdjieff's explanation of the practice of circumcision, we

encounter a good deal more interpretive difficulty. I don't have room

to examine possibilities in this post, lest it become overly long, but I

do have the following observations.

Gurdjieff had a habit of

burying his analogies deep within apparently reactionary diatribes

against contemporary morals and sexual practices. Consider, for example,

his insistence that aberrant sexual practices excluded a man from the

possibility of development, as recounted in

"In Search of the Miraculous."

This

stands in such stark contrast to his known association as the teacher

of a group of professed lesbians that we can only conclude the man

followed the adage "do as I do, not as I say." As if that were not

enough, Gurdjieff's own sexual peccadilloes amply demonstrate a flexible

attitude toward sexual morality.

Those who try to argue these

facts away are invoking the same willful ignorance we see from those who

would like to interpret the Bible literally. Of course, there are such

people, and they are welcome to their opinions. I prefer to use my

mind in a more concise manner.

In doing so, when I examine

Gurdjieff's discussion of circumcision and masturbation, I am forced to

conclude that he is burying a very serious teaching about inner work

within what appears to be an obvious outer circumstance. I believe that

he specifically chose controversial subjects and said controversial

things about them in order to provoke people. Using this clever

mechanism, reactionaries and dogmatists are reflexively turned away,

their attitudes themselves effectively depriving them of the opportunity

to penetrate his teachings.

In this sense, in order to

understand Gurdjieff's more outrageous and inflammatory passages--which

are not by any means in short supply--, we have to do what he always

told his pupils to: throw out every association we bring to the matter,

dismiss the obvious, and open ourselves to a new possibility.

In

doing so, we have to use all of our parts -- not only the one that

produces the emotional reaction, which is so easy to have and to obey,

but also the gut instinct of our body and the intelligence of our mind,

which will

both tell us--as any

serious Gurdjieff student already knows--that the man was never as

stupid as he appears to be in passages like this.

His exact

meaning may be difficult to penetrate, but I believe Paul's letter to

the Romans gives us a point of entry to the question.

May your roots find water, and your leaves know sun.

In this particular post I am just going to speak frankly and directly about my own life today, and exactly how I experience it.

In this particular post I am just going to speak frankly and directly about my own life today, and exactly how I experience it.